- Home

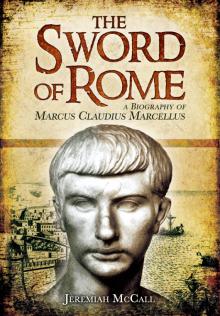

- Jeremiah McCall

The Sword of Rome

The Sword of Rome Read online

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright © Jeremiah McCall 2012

ISBN 978-1-84884-379-0

Digital Edition ISBN: 978-1-78346-156-1

The right of Jeremiah McCall to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11pt Ehrhardt by

Mac Style, Beverley, E. Yorkshire

Printed and bound by MPG

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation,

Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Pen & Sword Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime,

Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing

and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Introduction

List of Maps

List of Diagrams

Chapter 1: The Early Career

Chapter 2: Hannibal and Campania

Chapter 3: Syracus

Chapter 4: The Political Battle for Syracuse

Chapter 5: The Final Italian Campaigns

Conclusion

Appendix: Marcellus’ Record by Comparison

Notes and References

Bibliography

For Olivia

Introduction

There were few names from the middle Republic that were better known to later generations of Romans than Marcus Claudius Marcellus. ‘Sword of the Republic’ he was labeled by one writer for his audacity in battle,1 and he secured a reputation for valour with generations of Romans. Yet for all the consideration the Romans gave to their hero Marcellus, there exists no modern biography of him. Such a study is worthwhile, however, because Marcellus’ military and political career gives modern readers an excellent vantage point from which to view the military and political struggles of the Romans in the late third century BC and the role of military successes in the aristocratic culture of the Roman Republic. For readers relatively new to the military and politics of the late third century Republic, Marcellus provides perhaps the best point of access; for those familiar with the period, Marcellus offers a different perspective. Indeed, his military honours were unmatched by any other aristocrat of the middle Republic.

He was of the generation that fought in the First and Second Punic Wars, the greatest of the struggles against Carthage to dominate the Mediterranean. As Plutarch, a later biographer, put it:

They were the foremost Romans of his generation. In their youth they campaigned against the Carthaginians for the possession of Sicily: in their prime they fought against the Gauls for the defence of Italy itself, and as veterans they found themselves matched once more against the Carthaginians, this time under Hannibal. In this way they never enjoyed the relief from active service which old age brings to most men, but because of their noble birth and their prowess in war they were constantly summoned to take up new commands.2

Plutarch, like most Roman authors, tended to wax more than a bit poetically on the nobility and prowess of the old Romans, but he still had a point. Marcellus’s career and reputation from early adulthood to his death in the saddle, were based on his military exploits. As a young soldier fighting in Sicily he won a reputation for skill in single combat. When first elected consul, one of the two chief military and political officials of the Republic, he earned the grand victory celebration known as a triumph for soundly defeating a Gallic tribe in battle. Rarer still, he slew the Gallic king Virdumarus in single combat on that day when the Gallic army crumbled and earned the spolia opima, an honour, according to Roman antiquarians, that had only been earned by two others: a semi-legendary consul two centuries earlier and Romulus himself, the even more legendary founder of Rome. When Hannibal of Carthage brought an army across the Alps and inflicted a series of disastrous defeats on Roman armies (218–216BC), Marcellus preserved a ray of hope for the Republic by being the first to check Hannibal’s string of victories in a skirmish outside the central Italian city of Nola. The war against Hannibal continued, and Marcellus soon won a special military command by the grant of the Roman people; by 214BC, he had won the consulship again. Now his task was to return to the island of Sicily, where he began his military career, and subdue the powerful rebel city of Syracuse. After several years of campaigning, the Roman armies under his command occupied Syracuse and, at Marcellus’ orders, plundered the city. The wealth was carried through the streets of Rome in his second triumph, and used to decorate the city and fund the construction of his victory temple to the gods Honos and Virtus. His exploits, and the fascination with the period when the Republic went from a regional power to controlling a sizable part of the western Mediterranean, made Marcellus a fascinating subject for Roman writers. He remains so today.

For Romans of the Republic who were interested in the history of the aristocrats who led them, Marcus Claudius Marcellus stood out. Simply put, he had one of the most distinguished military and political careers in the Republic, one that dwarfed those of most who came before or since. By the time he died in 208 BC, the victim of a Carthaginian ambush, he had won election five times to the consulship, a feat matched by a small handful and topped once during the four centuries the office existed in the Republic. He was a field commander for nine consecutive years during the struggle against Hannibal, surpassed in this record only by Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, who defeated the great Carthaginian general Hannibal himself on the plains of North Africa. Consequently, Marcellus’ career and exploits became the stuff both of history and legend for later writers. The late Republican politician and orator, Cicero, contrasted Marcellus as a model of honour and moderation with the corrupt governor Verres. The grand historian of the Republic, Livy, emphasized his tenacity on the battlefield and his dogged pursuit of Hannibal when the Republic seemed on the verge of collapse. For Frontinus, that recorder of military stratagems in the early empire, Marcellus was a consummate strategist. Silius Italicus was inspired to capture Marcellus’ exploits in verse. The Greco-Roman moralist Plutarch recorded Marcellus’ deeds to illustrate to his audience the virtues of a simpler time. Nor are these the only examples; Marcellus’ deeds were trumpeted by the Romans for the better part of 1,000 years.

None of this record of praise does anything to alleviate the problem of accurately representing Marcellus’ life and career, the problem posed by the available evidence and its sources. It is a problem central to any historical analysis of the Roman Republic and its men and women, one which many approaching the history of the Republic may not fully appreciate, and one that must be exposed before looking too carefully at the records for Marcellus.

Modern readers interested in current events and recent history, modern figures and movements, are aware that, if anything, there are too many records, too many documents, too much information available. In addi

tion to the mountain of print resources, there is a digital Everest of blogs, forums, and tweets; YouTube videos; Facebook profiles; WikiLeaks; and so on. A staggering number of records exist for all but the most private, intimate, or casual events and their causes. Someone wins the lottery, and the event and the winner’s reactions are captured on local news, blogged about, twittered about, perhaps even disseminated through a home video on YouTube. A politician commits an indiscretion, and hundreds of takes on the situation spread across the globe, fuelled by the internet. Resistance and revolution erupt in countries like Iran, Egypt, and Libya, and we can access a constant stream of information not only from 24–hour news feeds, but from the activists themselves on social media sites and even websites custom crafted for spreading movements. Celebrity foibles, crimes, political and military decisions, religious crusades, the records and patterns of private citizens, if it happened in anything but the most private or banal of arenas – and sometimes even then – broadly speaking, the records exist for it. While the countless number of human actions and interactions on any given day insure there are many more undocumented events than documented, even in the modern world, the point is still well made: students of the modern world have access to more evidence than they can possibly use.

The Roman Republic, in contrast, though one of the better documented periods in ancient history, left a paltry few records. This is the case for even the best documented figures in the ancient world, and even more so for only adequately documented figures like Marcellus. Consider the problem. He lived between approximately 268BC and 208BC, during a period generally called the middle Republic. (Readers should note that from here on, unless otherwise indicated, all dates are BC.) We are reasonably certain of his death but know nothing about his birth. We do not know directly how he felt and what he thought about anything, why he entered the sphere of politics, how he viewed himself. We know he had a son of the same name, but do not even know the name of his wife. The evidence available for this period and its sources are simply too thin. There are essentially no primary sources, no eyewitness accounts for anything that Marcellus did or said. Indeed, with very few exceptions, there are no surviving eyewitness versions of anything that happened in Rome during most of the Republic – the end of the Republic in the first century being the notable exception. This does not mean, however, that Marcellus and his contemporaries wrote no letters, speeches, proclamations, perhaps even diaries; far from it. It’s simply the case that whatever was written by those who were there in the middle Republic is mostly lost.

Those studying the period and the person, therefore, need to rely on the accounts of secondary sources, later Roman writers who described, analyzed, and interpreted the actions of Marcellus and his contemporaries. Here too historians run into trouble. The Romans themselves did not even write history – in the sense of evidence-based, narrative interpretations of their people’s past – until after Marcellus had died; the first to do so was the Roman senator Fabius Pictor, who began writing a history of Rome – in Greek, as it happened – around 200. Fortunately for this study, Fabius was a senator during the Second Punic War (218–201), a conflict in which Marcellus played a critical role. He would have been at senatorial meetings with Marcellus, and witnessed the man in speech and action. Sadly, Fabius’ history is lost to us. It exists only in the form of a few passages quoted here and there by later Romans. It is not clear, then, how much he wrote or did not write about Marcellus – indeed it is not clear whether Fabius’ history went past 217.3 The same can be said for the second known historian of Rome, Marcus Porcius Cato. Cato the Elder, as he became known, served as a young military tribune under Marcellus at Syracuse4 and went on to have a highly distinguished career in politics of his own. He wrote the Origines (‘Origins’), a history of Rome. His account is also lost and his surviving manuscript on the management of a plantation, though precious for what it does tell historians, offers nothing directly about Marcellus. This pattern continues into the second century. A growing handful of Roman historians practiced their craft, so far as we know all of them senators, and nothing but fragments of their works survive. Perhaps these sources provided detailed, credible information about Marcellus and served to bolster the accounts of later writers. There is simply no way to know, however, and any strong claim based on such a speculation is a house built on sand.

The earliest surviving source to provide any sort of detailed information about Marcellus, then, is Polybius.5 He was a politician and military commander in the Achaean League, a federation of Greek city states that ran afoul of the Romans in the 160s. Polybius was one of 1,000 hostages taken by the Romans to Italy to guarantee the Greeks’ good behaviour. Polybius, unlike most of the other hostages, had the good fortune to become a mentor to a young Roman aristocrat from a distinguished family, Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus. As a result of this relationship, Polybius was able to travel in important political and military circles, observing in great detail the workings of the Republic and its people. He crafted what he had learned over the years into a history of the Romans in the third and second century. His stated goal was to explain to Greek readers everywhere – and Greek was the common language of the educated throughout the Mediterranean east of Italy – why and how the Romans had come to dominate the Mediterranean so swiftly. On the bright side, Polybius was in a position to have spoken to people who witnessed the great war against Hannibal, and indeed he claimed to have done so – though at least forty, if not fifty or sixty, years had passed since that struggle. When it came to Marcellus, however, Polybius seems to have made some effort to dim that Roman’s achievements, particularly when those achievements threatened to make Marcellus appear more distinguished than members of the Cornelius Scipio family, Polybius’ patrons. The context within which Polybius wrote his history illustrates that for the ancients, history was an important means of justifying and explaining the present and could be all the more slanted because of that.

The next surviving accounts of Marcellus come in the various references found in Cicero’s writings. Marcus Tullius Cicero (c. 106–43) was a Roman politician and orator at the very end of the Republic. Though never the most powerful of aristocrats, he had a full career and was wholly invested in the struggles that eventually ended in the collapse of the Republic and the creation of a monarchy, the Empire. Perhaps even more than the historians, however, Cicero seemingly always wrote to persuade his audience into some course of action; his references to Marcellus, accordingly, are tailored to fit his rhetorical purposes. The most straightforward example of this comes from Cicero’s speeches prosecuting the Roman governor Verres in 70. Verres was the governor of Sicily, a province in which Marcellus had spent several years during the Second Punic War. Cicero charged that Verres had milked the populace of Sicily and generally behaved tyrannically. When Cicero refers to Marcellus, who had sacked the rebellious Sicilian city of Syracuse and effectively placed the eastern half of the island under direct Roman control, he uses him, somewhat surprisingly, as a model of restraint and honour in a time of war, in order to emphasize Verres’ alleged excesses and deceits in a time of peace. Years later, in a work on reading the signs of the gods, Cicero calls Marcellus the ‘best of the augurs’, those priests charged with determining the signs.6 In general, Cicero seems to have believed, or wanted at least, Marcellus to represent a military man who was nevertheless respectful of the traditional institutions and values of the Romans, something that Cicero often found lacking in his contemporaries like Pompey, Caesar, and Antonius. So one must read Cicero’s remarks about Marcellus with care, trying to filter out Cicero’s first-century read of a third-century Roman.

As is so often the case when studying anything in the early and middle Republic, the main narrative account for Marcellus, both in terms of length and completeness, comes from Livy. It is particularly important, then, to gain some sense of who this writer was, for so much of our evidence about Marcellus is filtered through him.7 Titus Livius was a Roman of letters and book

s born around the year of Julius Caesar’s first consulship (59) and a child when the civil war between Caesar and his enemies in the senate broke out. During Livy’s youth Caesar was murdered (44), leaving his adopted son Octavian and his trusted lieutenant Marcus Antonius vying for control of the failing Republic. Under these men many Roman citizens were arbitrarily declared to be public enemies and slaughtered, including Cicero, and a series of new civil wars broke out. When Octavian crushed Antonius at the battle of Actium (31) and became the last warlord standing, Livy was about twenty-five. It will suffice to say that Livy came of age during the disintegration of the Republic, a time of civil war, and life-or-death domestic political wrangling for many Romans. Small wonder, then, that Livy began his monumental history of Rome, Ab Urbe Condita (‘From the Founding of the City’), with this clear declaration of purpose:

I invite the reader’s attention to the much more serious consideration of the kind of lives our ancestors lived, of who were the men, and what the means both in politics and war by which Rome’s power was first acquired and subsequently expanded. I would then have him trace the process of our moral decline, to watch, first, the sinking of the foundations of morality as the old teaching was allowed to lapse, then the rapidly increasing disintegration, then the final collapse of the whole edifice, and the dark dawning of our modern day when we can neither endure our vices nor face the remedies needed to cure them. The study of history is the best medicine for a sick mind. In history you have a record of the infinite variety of human experience plainly set out for all to see. In that record you can find for yourself and your country both examples and warnings; fine things to take as models, base things, rotten through and through, to avoid.8

The Sword of Rome

The Sword of Rome